Across the Mexican Line

Across the Mexican Line

When it comes to saving silent films, we all have to accept that we win some and we lose some. In the last few months we have discovered that one known film of Alice Guy's, Across the Mexican Line was too faded to preserve, a great loss for scholars of early cinema. But three other recently found films are well on their way to being saved.

Across the Mexican Line, (Solax 1911) which I attribute to Guy as director based on the date of release and stylistic choices, was described by one reviewer as follows:

“Across the Mexican Line” (Solax): This story is based upon the imbroglio in Mexico. It details a love story, coupled with the thrilling adventures of a woman spy. Apparently the Mexican general did not get the information he wanted, and the prisoner was recaptured by the American troops. The climbing of a telegraph pole and sending a message from its top is a novel stunt, which pleased the audience. The situations are also interesting.

The "imbroglio" of course, refers to the Mexican Revolution led by Pancho Villa. “The situation” referred to is an interracial romance. Across the Mexican Line was probably shot in the vicinity of the Gaumont Flushing studio in Queens, N.Y., The NFTVA has had the film elements for years, but when they finally tried to preserve the film so that it could be exhibited they discovered it was unsalvageable. It's a terrible loss, because the unique story elements would have made it a very interesting film to study.

The good news is that three other recently discovered films are in the process of being saved. Parson Sue, is the only known copy of a one-reel 1912 comedy by Alice Guy Blaché. Larry Benaquist, KSC film professor emeritus, has been awarded a grant from the National Film Preservation Foundation (NFPF) to restore another of the films from the “Nelson Collection,” which are now in the possession of Keene State College. The Nelson Collection is one of those legendary finds: a trunk full of early films languished in a barn for years, eventually discovered to be full of treasures.

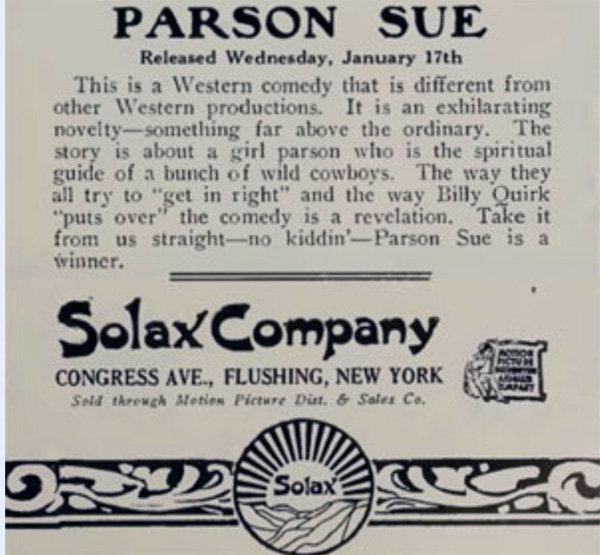

Parson Sue

Parson Sue

The Alice Guy film found there is Parson Sue, a "Eastern-Western" as I dubbed them in my book, Alice Guy Blaché, Lost Visionary of the Cinema.

Before 1912 trade papers used the term 'western' in a descriptive sense, as in the phrase 'Wild West dramas'. At that time the films that today would be called 'Westerns' were known under various genre categories: military films, Indian films, sometimes even 'Western dramas' and 'Western comedies'. Apparently, the first appearance of the term 'Western' to describe a film generically appeared in The Moving Picture World on July 20, 1912. Ironically, the westerns shot in and around Fort Lee had their heyday in 1911; by mid 1912 the western 'fad' appeared to be over. According to a variety of articles and editorials in The Moving Picture World, the audience was tired of them. The use of 'Jersey Scenery' especially exasperated one writer in The New York Dramatic Mirror. A few companies kept making them, of course, but more and more of these were satires, which demonstrates that the genre, indeed, had reached maturity. Of course, the migration of film companies to California brought spectacular light and landscapes, real Indians, real bronco riders, real Mexicans and stars like Tom Mix and William S. Hart. to the genre, giving it a new life by 1915.

Alice Guy Blaché had inaugurated her film company, Solax, in the fall of 1910, in Flushing, NY. She discovered that the Cheyenne Days Company troop of cowboys on hiatus between Orpheum Circuit engagements when she was in Ft. Meyer, Va., supervising the production of some military films. She told The Moving Picture News that she hadn't thought of making a western until she saw these bronco riders in action. This seems like a rather disingenuous remark on her part, given the high demand for Westerns. The Cheyenne Riders starred in The Girl and the Broncho Buster (Solax, 1911) which was released July 14, (now a lost film) and the next Solax western, Outwitted by Horse and Lariat (Solax 1911, released July 28th) (still extant) a film I attribute to Guy, as Melville was directing military films at that moment.

In Outwitted by Horse and Lariat Vinnie Burns, who played Florence in Greater Love Hath No Man, the older sister in Two Little Rangers and got friendly with a tiger in Beasts of the Jungle, plays the heroine that punches 'SOS' onto a leaf with her hairpin after she has been kidnapped by Mexican bandits. Vinnie’s lover and rescuer is played by a bronco rider, Otto Kline, who swoops down into the enemy camp and lifts her up onto his galloping horse with one arm, and the other members of his troupe who used their lassoes to good effect. In her autobiography Guy said that she and her regular actors all learned how to use the lasso from these broncho riders.

After Outwitted Solax continued to release military films on a regular basis, most of them directed by Wilbert Melville. Solax released two films that would probably qualify as Westerns today in the fall of 1911, which have not survived: Percy and His Squaw, released October 25, 1911, and Only a Squaw released November 17, 1911.

Parson Sue was released January 17, 1912, and it was the first Solax film to feature the newly hired Billy Quirk, a veteran of Biograph.

The Solax promotional summary for the film in Moving Picture World describes the film as a “Western Comedy” that achieves its hilarity without “resorting to moss-eaten methods:”

The story is about a bunch of cowboys who feel that they need the spiritual leadership of a parson. They send for one, and all go to the station to receive him. The boys keel over in astonishment when they find that the parson is a girl. Of course the chivalrous cow-punchers, who live in a section where the delicate influence of a woman is scarce, fall over themselves in an attempt to “get in right” with the new parson.

As time goes on, the new parson is the center of a plot which is laid by a villainous cowboy. The plot fails and Parson Sue is rescued by her lover at the expense of a bullet wound, which almost proves fatal, but Sue’s nursing brings her rescuer around all right.

This is the first release in which Billy Quirk appears. The comedy is infectious. Billy puts things over in his inimitable way.”

A review that appeared in Moving Picture World on January 20th makes it clear that much of the comedy comes from the contrast between the Parson’s authority that comes from her femininity as well as from her position as spiritual leader:

…the parson loses no time in starting a campaign for the defeat of Satan. She begins by posting a sign near the town horse-trough to the effect that ‘Cleanliness is next to Godliness.’ Of course the boys see the sign and immediately there is a sudden disposition among them to make use of soap, water and brush.

How does Parson Sue compare to Alice Guy's other westerns? Unfortunately, we can't compare it to Across the Mexican Line, a now-lost film that was nearly saved, but we do have a few others, such as Algie the Miner (released February 28th, 1912), directed by Edward Warren and Harry Shenck, with Guy credited as "producer and directing supervision." The Solax ad summarizes it as follows:

A Billy Quirck comedy. Algie is a "sissy boy" who has as much backbone as a jelly fish. When Algie falls in love and finds that his sweetheart objects to his "personality" he goes West and after several ludicrous experiences and hard struggles he becomes a "man." A comedy with strong character portrayals.

Guy pushed at the boundaries of the Western genre when she moved from having a woman using her smarts to get herself saved, to a woman as a parson and inspire cowboys to reform, to a woman throwing her own lasso and shooting her own gun. The latter happens in Two Little Rangers, sometimes also known as The Little Rangers (released August 12, 1912). The final triangular tableau, reminiscent of a pietà arrangement, is typical of Guy's endings for her action films; we see a very similar tableau at the end of Greater Love Hath No Man (Solax 1911). At this point she had pushed the genre as far as she could.

By 1913 Westerns with a “Jersey setting” were no longer being made, with the exception of parodies like Playing Trumps, (August 1912), another film thought lost but recently we discovered that Katja Raganelli has a print in Germany. Billy Quirk plays suitor to Blanche Cornwall, but her attentions are always diverted by the more elegant and more sophisticated entertainments offered to her by his two rivals, one played by Darwin Karr. Billy's winning strategy is to hire a film production company. He instructs the film director carefully. While Blanche is out on a drive with his two rivals their car breaks down. A gang of "Mexicans" (white actors in makeup) assault the car and take Blanche hostage. Billy arrives, shoots into the air, and rescues Blanche. His two rivals both react with perfect cowardice.

Frame from Tramp's Strategy, courtesy The Eye Institute.

Frame from Tramp's Strategy, courtesy The Eye Institute.

Two other films by Alice Guy were recently discovered: The Tramp's Strategy, which is being preserved by The Eye Institute in The Netherlands. Here is the review that appeared in Motion Picture News April 8, 1911 Vol. IV No. 14; p. 17

Tramp Strategy Solax Release April 12

Dan Wellington “objects” strenuously to his daughter’s marriage with Richard Darlington. The father finds the latter in the arms of his daughter and puts him out of the house. The much abused lover is followed out of the house by his sweetheart and maid. The latter conceives a brilliant idea whereby the lover is to assume the disguise of a tramp and rescue his sweetheart from being ground beneath the wheels of an automobile.

While the plot is being consummated on one side of a hedge fence, two tramps are asleep on the other side. The excited voices awaken them and while the maid recites the proposed plan the tramps are working on one of their own. After leaving the two girls to go in search of a costume, Darlington is overpowered by the two tramps and hustled off to a lonely hut where he is detained. One of the tramps plans to go in Darlington’s stead and do the hero work.

The communications that arise from the situations can well be imagined but everything is arranged so that the unhappy lover gets the girl and the policemen get the tramps.

The Coming of Sunbeam

The Coming of Sunbeam

Last but not least, the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., has a print of The Coming of Sunbeam. It is not clear if the LOC plans to preserve it, though scholars and film preservationists would love to see it premiered at the Alice Guy Conference organized by the University of Maryland that will take place in November of 2012.